See the Meeting Slide Show Here

Chief justice of the Land Court – Letter to the Legislature

The subject of state property tax lien foreclosure is currently under a national spotlight as the Supreme Court has ruled that tax foreclosure processes like the one in Minnesota are unconstitutional.

“Closer to home, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court previously has passed upon the Commonwealth’s existing tax foreclosure statutory scheme in Kelly v. City of Boston, 348 Mass. 385 (1965), holding that a former owner was not entitled to any payment representing the surplus fair market value of the property exceeding the tax liability.~ The Land Court, as a trial court, is bound by that precedent unless it is changed.”

“Moreover, public auctions, particularly those which occur as distress sales under court directive, do not generally maximize the sale proceeds… But the learned experience with mortgage foreclosure sales is that public auctions under statutory power of sale seldom result in substantial returns of equity to foreclosed homeowners. They are distress sales, and do not often produce sale prices approaching those which might be seen if the property were fully exposed to the market in a conventional way.”

“The current system certainly causes taxpayers to lose the equity they have built up in their homes if they do not redeem, and this can result in catastrophic loss when the owners are unable to raise the funds they need to redeem. But ordering a sale of the property may not help much with this, if the sale, because of its terms and the fact that it is a distress sale, yields a price well below the true market value of the property. The property will be liquidated and the actual value of the equity will end up in the hands of the buyer, who was able to acquire title at a below market price, rather than being returned to the taxpayer. ”

“In many cases, however, the property’s title remains with the municipality, which often keeps the title, at least for some time longer. This allows the opportunity for the taxpayer, even after foreclosure, to work out an

arrangement with the municipality to pay off what is then due and regain title. The chance to do that is greater within the first year after the foreclosure judgment, when the court has discretion to order vacation of the foreclosure judgment. But even after the year passes, the judgment can be vacated with the assent of the city or town if it still holds title. Most municipalities in many cases do not seek to take a home for municipal use, or to realize the full equity value of the property. Most cities and towns just want to recover the delinquent taxes and the costs of the foreclosure, and will be open to allowing the judgment of foreclosure to be vacated.”

Gordon H. Piper

Chief Justice of the Land Court

Legislature’s inaction on ‘home equity theft’ hinders city tax foreclosures – New Bedford Light

Much More About Home Equity Theft Below

The U.S. Supreme Court handed down a landmark decision in Tyler v. Hennepin County finding a Minnesota county could not keep the excess equity it reaped after foreclosing on a woman’s condominium in order to resolve a tax lien.

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling last year, states that permit the practice have seen a wave of new litigation from homeowners looking to challenge it and efforts by lawmakers to reform it.

Most of the work going on right now is happening in the legislatures in various states. … Everyone’s trying to figure out how they’re going to navigate Tyler and what that’s going to look like.

Read the full Law 360 article here

Land Court Statement on Tyler v. Hennepin County, Minnesota

The amount that exceeds the tax debt owed is sometimes called the “home

equity.” The Supreme Court decided that when the taxing authority keeps these “excess” or “surplus” funds from the foreclosure sale, the authority has made a “taking,” in violation of the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which says that government cannot take private property without paying just compensation.

Current Massachusetts tax laws do not address if or what money is owed to a property owner after the foreclosure is final. But the Tyler case makes clear that, under the U. S. Constitution, property owners will be owed compensation from a tax foreclosure—if the property taken by the government is worth more than the tax debt owed.

Motion to Vacate – Land Court – Town of Bolton v DiPietro

Town of Lynnfield v. Owners Unknown, 397 Mass. at 474; (1986). Moreover, “[t]he purpose of those provisions is not to provide municipalities with a method of acquiring property for municipal purposes without paying the owner of the property fair compensation as in eminent domain proceedings. The redemption provisions were enacted by the Legislature to provide municipalities with a mechanism for the prompt collection of delinquent real estate taxes.” City of Boston v. James, 26 Mass.App.Ct. at 630 “the only legitimate interest of a town in seeking to foreclose rights of redemption is the collection of taxes due on the property, together with other costs and interest”.

Quoting from Tyler: “The principle that a government may not take from a taxpayer more than she owes is rooted in English law and can trace its origins at least as far back as the Magna Carta. From the founding, the new Government of the United States could seize and sell only “so much of [a] tract of land … as may be necessary to satisfy the taxes due thereon.” Act of July 14, 1798, §13, 1 Stat. 601. “if a whole tract of land was sold when a small part of it would have been sufficient for the taxes, which at present appears to be the case, the collector unquestionably exceeded his authority.” Stead’s Executors v. Course, 4 Cranch 403, 414 (1808) (Marshall, C. J., for the Court).”

G.L. c. 60, §64 is unconstitutional on its face and as applied to Mr. DiPietro. Thus, this entire action is, at present, a legal nullity. It is respectfully submitted that the orders and judgments entered in this case are void ab initio since this action is wholly predicated upon a constitutionally infirm statute (G.L. c. 60, §64). It must be recalled that “[i]f the court which renders judgment has no jurisdiction to render it, either because the proceedings, or the law under which they are taken, are unconstitutional, or for any other reason, the judgment is void and may be questioned collaterally…” In Re Neilson, 131 U.S. 176, 182 (1889).

What’s Happening in Superior Court?

In the wake of the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Tyler v. Hennepin County, 598 U.S. 631 (2023), Massachusetts municipalities face a difficult circumstance: The state statutory scheme establishing a process for municipal foreclosures on real property is clearly unconstitutional (both facially and applied); the Legislature seems to understand this problem and has held hearings to address it; but the Legislature has not yet amended the relevant statutory sections in G.L. c. 60. Facing municipal tax foreclosure, Plaintiff Ashley Mills, a 25-year-old single mother from Springfield, sought a ruling from the Supreme Judicial Court conforming the tax collection statutes to the standards set by the United States Supreme Court in Tyler. The Supreme Judicial Court in turn transferred the case to this Court for disposition.

Have you ever miscalculated a bill? Typically, a late fee or a strongly worded warning follows. But do you know what happens if you miscalculate and underpay your property taxes— even by just a few dollars? In Massachusetts, 11 other states and DC, the government will seize your property, sell it, and leave you with nothing.

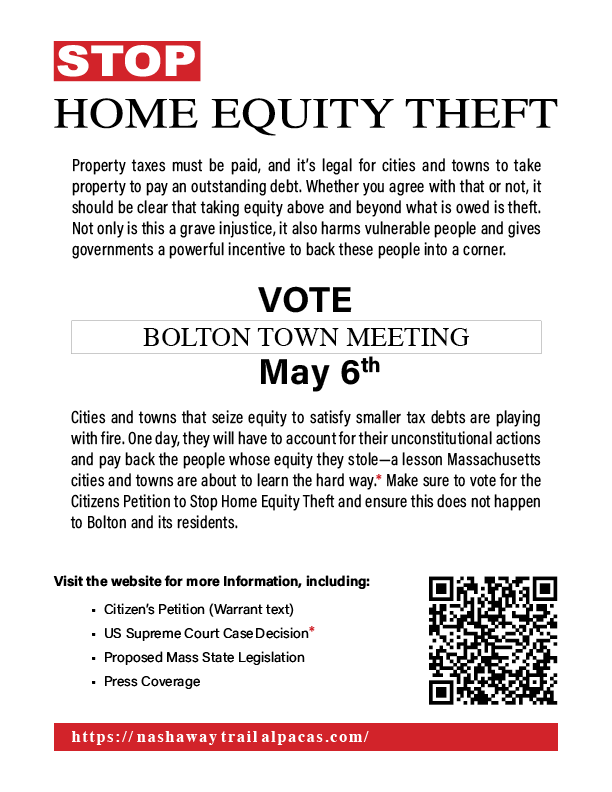

Property taxes must be paid, and it’s legal for governments to take property to pay an outstanding debt. But the government shouldn’t keep any more money beyond what’s owed. The rest is your property: home equity that you’ve worked hard to build.

“Home equity theft is robbing thousands of people of their homes and all the equity they’ve built,” The laws have allowed local government officials to take homes that “have been in families for generations” and “leave some people homeless over tax debts that amount to less than one percent of their property’s value.”

“A system that allows governments and private investors to take more than what is owed creates a perverse incentive to work against the homeowner — not with the homeowner — to get the tax debt paid.” Under state law, cities and towns can sell or keep tax liens on delinquent properties. The lienholder — whether it’s a local government or investor — can file for foreclosure once the debt is six months old. Upon foreclosure, the lienholder gets a deed to the property and can keep or sell it. A lienholder can keep profits from the sale, under the current law.

This contrasts with what happens when a bank forecloses on a property. In that case, the bank sells the property, deducts from the proceeds what it is owed, then returns any remaining equity to the former owner. “When a debt-holder takes more than what’s actually owed that’s usually called theft, but in this context it’s actually endorsed by state law,”

“We’re not done in Massachusetts, not until this law is declared unconstitutional and stricken from the books.”

Violating the Spirit of America: Home Equity Theft in Massachusetts

Read all the details about what the Town of Bolton has done. DiPietro v. Town of Bolton Complaint

The Massachusetts Land Court issued a statement on the U.S. Supreme Court unanimous Tyler v. Hennepin County ruling: “Under the U.S. Constitution, property owners will be owed compensation from a tax foreclosure — if the property taken by the government is worth more than the tax debt owed. Property owners who are undergoing tax foreclosure should be aware of their right to claim compensation for their ‘home equity’ — the excess value of the property above the amount of the tax debt.

California-based Pacific Legal Foundation sent a letter to the president of Greenfield’s City Council: “We sent correspondence to Greenfield Treasurer Kelly Varner, urging the City to immediately halt any property tax foreclosures that may result in the theft of home equity. Each property owner who is deprived of equity under the current scheme has a takings claim against the government — exposing the public to millions of dollars in imminent claims.”

Case law precedents recognize that a taxpayer is entitled to the surplus in excess of the debt owed. The plaintiffs are seeking compensatory damages, punitive damages, treble damages, costs and attorney fees. The city should settle such claims quickly to avoid mounting legal costs.

Greenfield Recorder – Pushback: City flouts high court on ‘home equity theft’

Click here to read more Press Coverage

Home Equity Theft Violates Property Rights

In Massachusetts, if a homeowner falls behind on or mistakenly underpays their property taxes and the debt remains unpaid, an investor can bid for the right to take the home. Municipalities can sell a tax lien on the home to an investor, who pays the tax and then has the right to collect the debt at a generous 16% annual interest rate.

If the homeowner cannot pay the debt plus interest and fees, the tax lien allows the investor to foreclose and take the entire property. It doesn’t matter how much home equity the owner had, or how little tax they owed; the investor can take everything.

Alternatively, the municipality may hold on to the tax lien, sell the home itself, and keep all the equity as a windfall for the government. See Appendix 2 for a detailed explanation of the Massachusetts home equity theft process.

An Unconstitutional System

Beyond being patently unjust, home equity theft is unconstitutional under the United States and Massachusetts Constitutions. Although the Supreme Court of the United States and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court have not yet written directly on instances of home equity theft in Massachusetts, the Takings Clauses of both constitutions prohibit the government from taking property for public use without just compensation.

Ultimately, when the government takes more than it is owed, it also takes on an obligation. It must pay the former owner for the excess property value it took or it must sell the property to the highest bidder and return the extra funds to the former owner. Failure to abide by this traditional protection violates the Federal and Massachusetts Takings Clauses.

Of course, tax collection is considered an important municipal function in Massachusetts. But cities cannot go beyond the confines of the federal and state constitutions by taking equity in addition to what homeowners owe in taxes, interest, and fees. Because victims of the tax foreclosure process can seek compensation in court, cities that seize equity to satisfy smaller tax debts are playing with fire. They will have to account for their unconstitutional actions and pay back the people whose equity they stole—a lesson Michigan counties are currently learning the hard way.

On May 25, 2023, the Supreme Court announced a unanimous decision in favor of Geraldine Tyler, ruling that home equity theft violates the Takings Clase of the Fifth Amendment. The Court explained that property rights are fundamental and cannot be erased by a state statute that redefines them out of existence. “The taxpayer must render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the decision, “but no more.”

Tyler v. Hennepin County | Pacific Legal Foundation

The US Supreme Court Tyler Decision

From the Massachusetts Attorney General

“[T]he property owner has suffered a violation of his Fifth Amendment rights when the government takes his property without just compensation, and therefore may bring his claim in federal court under [42 U.S.C.] § 1983 at that time.” Id. at 2168. This creates a possibility that, after Tyler, a tax lien foreclosure under Chapter 60 could create liability under Section 1983 for the involved officials. While the amount of compensation for a taking is similar under federal and state law, see Woodworth v. Commonwealth, 353 Mass. 229, 231-32 (1967), Section 1983 allows a plaintiff to recover attorneys’ fees and costs, 42 U.S.C. § 1988(b), and may in some circumstances result in personal liability that cannot be indemnified under state law. See G.L. c. 258, § 9 (providing that indemnification is not available for willful acts that cause constitutional violations). Even if a cause of action may lie for recovery under Chapter 79, the availability of such an action very likely would not foreclose an action under Section 1983. Knick, 139 S. Ct. at 2171.

The AG’s Full Amicus Brief here

What Can Others do to help? – Contact your state representatives

Legislation is pending in the Massachusetts House and Senate. Bolton Voters please contact your representatives and tell them you want them to support the following bills

H. 2937

An Act protecting equity for homeowners facing foreclosure

S. 921

An Act protecting equity for homeowners facing foreclosure

S. 1774

An Act relative to the surplus from a tax title sale

S. 1953

An Act relative to force sale of property by tax lien

S. 1876

An Act protecting homeowners from unfair tax lien practices by cities and towns